Science Without Belief

Pyrrhonism isn’t just compatible with science — it helped make science possible.

One of the criticisms leveled at the modern-day practice of Pyrrhonism is a claim that Pyrrhonism is incompatible with modern science and, therefore, Pyrrhonism should not be considered a viable philosophy of life for modern people to hold.

Hogwash!

Other ancient philosophies of life, such as Stoicism and Epicureanism, don’t get dismissed as dead because they’re incompatible with modern science. Those philosophies are given a pass on this point, despite the fact that Stoicism and Epicureanism based their claims about eudaimonia on their scientific claims - their claims about physical reality.

One type of pass admits that their science was bunk, but their ethical teachings stand fine on their own. Another type of pass claims their primitive science was directionally correct, and that’s good enough.

These passes are reasonable. The fact that the ancients tried to prove that their ethical propositions were true based on their understandings of the physical world, and those understandings have turned out to be wildly wrong, doesn’t require us to assume those ethical propositions must be wrong. For hundreds of years, people put those ethical teachings into practice and found them helpful.

What is unreasonable is the idea that Pyrrhonism must be held to a higher standard than Stoicism and Epicureanism are held to, and based on this standard, it can be concluded that Pyrrhonism is unlivable as a philosophy of life.

This essay is not going to ask you to give Pyrrhonism the kind of pass given to the modern adherents of the porch and the garden. Instead, its aim is to show you that Pyrrhonism’s critics are mistaken. Pyrrhonism not only meets this higher standard, the very reason the standard got raised is due to the virtues of Pyrrhonism.

Let's consider what the critics say. To my knowledge, the most vocal one on this issue has been Richard Bett, a long-time scholar and critic of Pyrrhonism. In his first published article on ancient Pyrrhonism in 1987, he concluded that it is difficult “to fathom the frame of mind in which this way of life could seem both possible and desirable,” and this is undoubtedly the reason “why Pyrrhonism never achieved anything like the popular appeal of Stoicism or Epicureanism.”1

In the final chapter of his shockingly mistitled book, How to Be a Pyrrhonist - a collection of some of his most notable academic papers - he concludes that it’s impossible to be a Pyrrhonist because the suspension of judgement the Pyrrhonists advocate has become unavailable to us, largely due to the progress of natural science. Modern science, he claims, has created “a huge, systematic body of findings… supported by massive evidence, that are not subject to equally plausible opposing arguments.” (p 234).

We modern Pyrrhonists have at least two ways of responding to this challenge. The first one I’ll present comes from my fellow Pyrrhonist Carneades.org, a prolific and popular publisher of explanations of philosophical ideas via YouTube videos - over 1,100 of them for his 159k subscribers.

Carneades.org takes the precaution of publishing under a pseudonym because he works in international development, sometimes in countries where Pyrrhonist views might get him fired or even imprisoned or put into danger. Socrates is welcome to his hemlock for his beliefs. Pyrrhonists are characteristicly more prudent.

Carneades.org details his response to this criticism of Pyrrhonism in his video, Using Science Without Belief, in which he makes a case for a perspective on science known as “Scientific Instrumentalism” - a perspective compatible with both Pyrrhonism and the functioning of modern science.

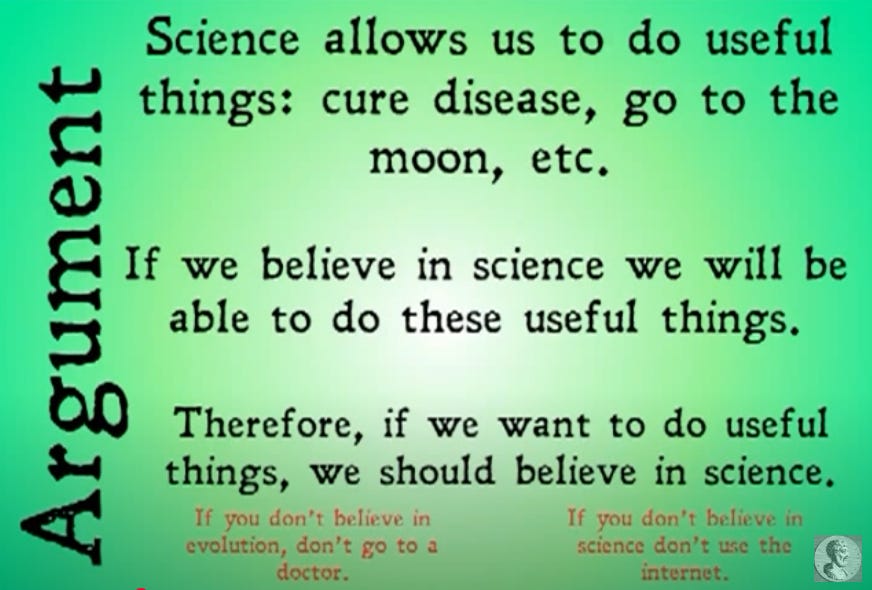

Here’s a screenshot showing how he opens his argument:

Carneades.org says that the second proposition is faulty. The correct way to think about it is that if we want to do useful things, we should use science. Belief is unnecessary.

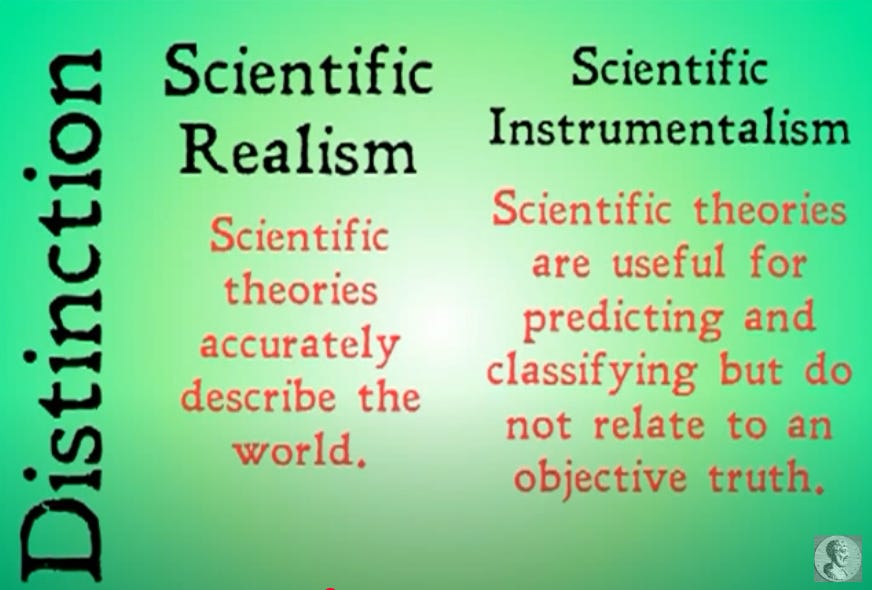

This faulty way to think about science results in “Scientific Realism.” He presents “Scientific Instrumentalism” as the alternative.

He then gives examples of how this works in practice. In his first example, he compares two ancient Greek farmers. One believes in the now-overturned theory that the Sun goes around the Earth. The farmer believes this theory tells him when planting and harvesting should take place. The other doesn’t believe the theory, but finds the predictions useful. While what’s going on in the heads of the two farmers is different, they behave in the exact same way.

In his second example, he presents two modern scientists, one who believes in the theory of evolution and in using it as a guide to developing cures for disease, and one who uses the theory for its predictive power, but without a belief that the theory necessarily accurately describes reality. Like the farmers, they behave the same way.

In both of these examples, the first character follows Scientific Realism and the second follows Scientific Instrumentalism.

Carneades.org goes on to say that “science is a method. It lets us do things. It is not something that forces us to know things.”

He concludes by citing the following from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Excluding naive realists, most scientists are fallibilists in Peirce’s sense: scientific theories are hypothetical and always corrigible in principle. They may happen to be true, but we cannot know this for certain in any particular case.

Watch the video. It’s only four minutes long.

As Carneades.org makes clear, Pyrrhonism is perfectly compatible with modern science. Bett’s criticism holds no water. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t Scientific Realists out there who believe otherwise. There are. Bett appears to be one of them. The point is that one need not accept their view on the issue of whether modern science makes the practice of Pyrrhonism untenable.

A second approach entails developing a better appreciation of the terribly faulty state of ancient science and logic, how Pyrrhonism arose in response to those faults, and how modern science is, in turn, a response to the ancient Pyrrhonists.

My most entertaining example of one of the flaws in ancient logic comes from Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. In what is perhaps the climactic scene of the novel/memoir, there’s a dramatic confrontation between the protagonist, Phaedrus, and the “Chairman for the Committee on Analysis of Ideas and Study of Methods.” (The Chairman is a thinly veiled reference to the University of Chicago neo-Aristotelian scholar Richard McKeon).

The confrontation starts in a classroom discussion of Plato’s allegory of the chariot with the Chairman saying,

“Now Socrates has sworn to the Gods that he is telling the Truth. He has taken an oath to speak the Truth, and if what follows is not the Truth he has forfeited his own soul.”

TRAP! He’s using the dialogue to prove the holiness of reason! Once that’s established he can move down into enquiries of what reason is, and then, lo and behold, there we are in Aristotle’s domain again!

Phædrus raises his hand, palm flat out, elbow on the table. Where before this hand was shaking, it is now deadly calm. Phædrus senses that he now is formally signing his own death warrant here, but knows he will sign another kind of death warrant if he takes his hand down.

The Chairman sees the hand, is surprised and disturbed by it, but acknowledges it. Then the message is delivered.

Phædrus says, “All this is just an analogy.”

Silence. And then confusion appears on the Chairman’s face. “What?” he says.

The spell of his performance is broken.

“This entire description of the chariot and horses is just an analogy.”

“What?” he says again, then loudly, ”It is the truth! Socrates has sworn to the Gods that it is the truth!”

Phædrus replies, “Socrates himself says it is an analogy.”

“If you will read the dialogue you will find that Socrates specifically states it is the Truth!”

“Yes, but prior to that – in, I believe, two paragraphs – he has stated that it is an analogy.”

The text is on the table to consult but the Chairman has enough sense not to consult it. If he does and Phædrus is right, his classroom face is completely demolished. He has told the class no one has read the book thoroughly.

There happens to be an inconvenient fact not mentioned in this story, probably because both Phaedrus and the Chairman were unaware of it. Many ancient thinkers believed that reasoning by analogy led to truth. Based on Socrates’ use of analogy, it appears that Socrates was likely one of those thinkers. And with that, the premises for this crisis in Pirsig’s story disappear. The Chairman could have dismissed Phaedrus’ concern by pointing out that even though we now know that Socrates’ reasoning was faulty, he believed it proved what he said was true.

Not that this would have rescued the holiness of reason - the target Phaedrus was aiming to take down. The claim that reason is holy does not stand if we know that said “reason” was contaminated.

What Phaedrus spotted was not rhetorical sleight of hand on the part of Plato (as he thought), but error on the part of Socrates (and/or Plato). No wonder Phaedrus came to hate the Greek classics

vehemently, and to assail them with every kind of invective he could think of, not because they were irrelevant but for exactly the opposite reason. The more he studied, the more convinced he became that no one had yet told the damage to this world that had resulted from our unconscious acceptance of their thought.

Incidentally, should you go looking for all of this in Plato’s Phaedrus you will find it is not nearly as clear and tidy as Pirsig makes it out to be. As I said, it’s my most entertaining example. Nevertheless, reasoning by analogy was a common method used to provide “proof” for the dogmas the ancient Pyrrhonists criticized (Outlines of Pyrrhonism 1.147).

Another target was reasoning by induction. Aristotle tells us that Socrates was “the first to set his mind on induction” (Metaphysics Book I, 987a29–b14). While Hume is well-known for pointing out the flaws of induction, the Pyrrhonists beat him to it by at least 1,500 years (Outlines of Pyrrhonism I.204). While Socrates was, for his day, an exceptional thinker, there are flaws in his reasoning that are easier to see now, thanks to the ancient Pyrrhonists.

So much for ancient logic. It was flawed, and some of the mistakes of the ancients are ingrained in our culture.

Now, let’s consider ancient natural science.

If one goes through Sextus Empiricus’ work Against the Physicists, one has to look hard to find any theory we would today consider to be true that Sextus argued had been rashly embraced by the dogmatists. An example of such a theory is the one that sweat is produced by invisible pores in the skin. But, if the ancients had microscopes, they would have been able to see those pores. It would not be a theory, but by Pyrrhonist standards, an evident fact about the phenomenon of sweating. Sextus elsewhere pointed out that the Pyrrhonists were not critiquing evident facts like this, such as where there is smoke there is fire, and where there is a scar there was once a wound; they were critiquing beliefs that went beyond the empirical evidence.

Many of the advancements provided by modern science are like this story about skin pores. The advancements are due to improvements in our ability to observe phenomena. As such, they are now and always have been fully compatible with Pyrrhonism.

In his book, The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science, Michael Strevens, Ph.d., a specialist in the philosophy of science, says that the key thing that distinguishes modern science from ancient science is that only one thing counts as universally acceptable in settling modern scientific disputes: evidence about the phenomena. Strevens calls this the “iron rule of science.”

While Strevens does not credit the ancient Pyrrhonists for the iron rule, Sextus repeatedly critiques ancient science for its failure to respect the observable phenomena, and he emphasizes that the Pyrrhonists take the observable phenomena as the criterion (Outlines of Pyrrhonism I.18-20, Against the Logicians I.29-31).

The ancient Pyrrhonists are the earliest adopters of the iron rule. As the iron rule of science rests on this foundation laid down by the ancient Pyrrhonists, it is therefore because of Pyrrhonism that we have modern science.

One reason this is not widely recognized is that the rule was transmitted by intermediary thinkers who didn’t credit the ancient Pyrrhonists. They may well not have been conscious of their influence. Another reason is associated with what Carneades.org points out. From the perspective of the Scientific Realists, the fault the Pyrrhonists point out is not visible. They think, like Socrates did, that we have secure access to the truth about reality - so secure one may safely swear to the Gods, pledging one’s own soul as security.

Socrates frequently reminded his interlocutors of the first Delphic Maxim: “know thyself.” Less frequently, he mentioned the second maxim: “nothing to excess.” He was not recorded to have mentioned the third maxim: “give a pledge and calamity draws near.”

We Pyrrhonists are much more cautious. Our idea of knowledge is limited to what we can observe about phenomena. Leaps to what reality is behind the phenomena remain conjectures, always open to refutations.

I suspect that one of the reasons Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance was such a popular book is that it revealed a calamity in the domain of values that got set into motion from Socrates’ pledge. We’re still struggling with that calamity.

But, there were other calamities, too. One that we tend to forget about is that excessive reverence for the reasoning of certain ancient Greeks was the cause of the near-stalling of scientific progress until the crise pyrrhonienne destabilized medieval Scholasticism, helping to ignite the Enlightenment.

It is not that modern science has made the practice of Pyrrhonism untenable. What’s untenable is the Scientific Realist view of the practice of science. It was acknowledging that the ancient Pyrrhonists were right in their criticisms of ancient science which revolutionized science.

The task now is for Pyrrhonism to revolutionize ethics.

Scepticism as a way of life and scepticism as 'pure theory'', in M. Whitby, P.R. Hardie, and M. Whitby (eds.), Homo Viator: Classical Essays for John Bramble. Bristol Classical Press and Bolchazy-Carducci, 49-57, at 56. 1987