Appended to most of the surviving manuscripts of the works of the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus is a short, mysterious philosophical work. The manuscripts give no title or author. It was perhaps obscure even in antiquity; only one other ancient text even hints that this work was known. It’s unclear why an ancient copyist thought this was worth preserving, and unclear why it was preserved along with Sextus’ works.

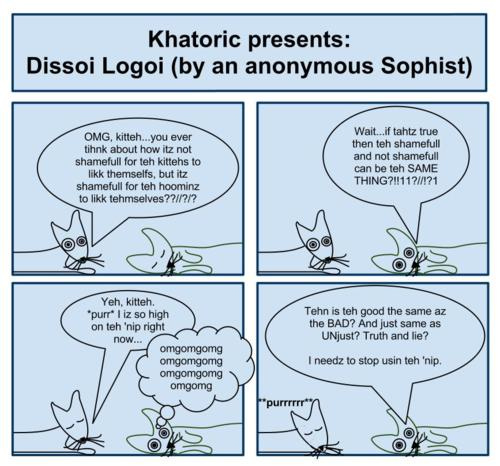

The work is now usually called Dissoi Logoi - “opposing arguments” - the subject of the work’s first sentence. It’s also called Dialex or Dialexeis.

The dialect of the text is odd. Only one other surviving text seems to be in that dialect - a variant of Doric. Doric was mainly spoken in northwestern Greece. This text includes elements of Attic and Ionic - dialects that were spoken in eastern Greece, in places not bordering where Doric was spoken. The Mediterranean is full of islands colonized by Greeks from elsewhere. So, it’s possible for an odd hybrid like this to have existed. Or perhaps the author spoke Attic or Ionic but was writing for a Doric audience, and so made mistakes. Or perhaps the oddness of the dialect was introduced by a copyist.

The text's date is also mysterious, but some things can be inferred from it to estimate a date range. The oldest possible date argued for is 457 BCE. The most recent is 338 BCE. So, the earliest date is when Socrates was a young man, and the latest is a decade after Plato’s death.

One thing that’s clear from the work is the philosophical school it belongs to. It’s Sophist. The Sophists get disparaged as peddlers of specious arguments who pretended to be philosophers but who were in fact just money-grubbing rhetoricians. While for some Sophists, that stereotype may have been true, but other Sophists were real philosophers - philosophers who taught virtue - philosophers who were victims of a smear campaign against them by Plato. Protagoras was a real philosopher, as was Gorgias. So was the author of the Dissoi Logoi.

The Dissoi Logoi has recently received fresh attention with the publication of Dissoi Logoi: Introduction, Critical Text, Translation, and Commentary by Sebastiano Molinelli. The author has tracked down and analyzed more of the surviving manuscripts than any prior scholar and has produced a new critical text, a fresh translation, and an in-depth analysis of this under-appreciated ancient text. If you do academic research on Pyrrhonism, this is a text worth asking your library to obtain a copy of.

Molinelli’s book makes me recall the book that won the 2012 Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt - not that it is anywhere near as entertaining or audacious in its claims, but it tells a similar story - in bare factual outline - about how an ancient text came down to us, and it investigates the mysteries of that text. Of course, Dissoi Logoi never had anywhere near the impact that Lucrecius’ On the Nature of Things had - but the works of Sextus Empiricus, to which the text was attached, did have that kind of impact - a fact strangely ignored by Greenblatt, whose work has been subsequently much criticized.

A long time ago, some copyist decided to add a copy of Dissoi Logoi to a copy of the works of Sextus Empiricus. Why attach a Sophistic text to a Pyrrhonist text? Why attach a text that was about 500 years older than the Pyrrhonist text? How did these two texts even end up in the same place that they might be copied together?

Sextus’ text has many elements that appear to have evolved from the Dissoi Logoi. For example, prominent in both texts is the idea of setting arguments in opposition with each other. The position Sextus takes about ethics - that good and evil do not exist by nature - has a great deal in common with what the Dissoi Logoi says in its first few lines.

(1) Contrasting speeches are made in Hellas, by those who philosophise, about what is good and what is bad. For some say that what is good is one thing, what is bad another; others say that they are the same thing, and that for some people this thing is good, for others bad, and for the same man sometimes good, sometimes bad. (2) I too agree with the latter group. I will refect, then, starting from human life, whose business is food, drinking and sexual pleasures. These things, in fact, are bad for those who are ill, but good for one who is in health and needs them. (3) And incontinence in these things is something bad for the incontinent, but good for those who trade in them and earn wages by them. Illness, further, is bad for patients, but good for physicians. Death is something bad for those dying, but good for undertakers and grave-diggers.

In Molinelli’s preface he says, “The work seems to have been known to Pyrrhonean philosophers Aenesidemus, Zeuxis, and Sextus Empiricus, which contributes to explaining its collocation at the end of Sextus’ codices.” One question Molinelli doesn’t explore, which I would like to take up here, is whether the Dissoi Logoi was known to Pyrrho. Even the latest proposed date of composition, 338 BCE, would have been when Pyrrho was about 20. Pyrrho didn’t return from India until at the earliest 325 BCE. So, at least according to the chronology, Pyrrho could easily have been influenced by the Dissoi Logoi.

I’ve been asked many times about why - if Pyrrho had been so influenced by his study of Buddhism while he was in India that borrowed some elements of it as the foundation of his philosophy - why didn’t he also import Buddhist meditation into Greece?

My speculation is that on one hand, Pyrrho recognized some constraints on what was possible to propose to his fellow Greeks. Meditation was not a traditional practice among the Greeks. Proposing a practice from the barbarians would be hard to sell. Nor could he propose anything that would seem to compete with established religion. A cult like the one established by Pythagoras was now out of the question.

On the other hand, Pyrrho may have had an epiphany in the process of working with the kind of contrasting arguments described in the Dissoi Logoi while also reflecting on the Buddhist Three Marks of Existence - on impermanence, the unsatisfactoriness that comes from instability, and the recognition that things lack inherent features to allow them to be categorized - they lack Aristotelian substance, they lack self-essence. Because contrasting arguments are built on things that are impermanent, unstable, unsatisfactory, and without firm logical distinctions, they have the potential to cancel each other. If they are allowed to cancel each other, a certain state of mind can arise, a state of not-knowing. As James Ford Roshi puts it,

When asked what is Zen, the Korean Zen master Seung Sahn said, “Only don’t know.” This is the great secret of Zen spirituality. And, frankly, the secret gateway for us all.

As Ford notes, this state is not unique to Zen; there is ample evidence that it can be found through certain Christian practices as well, and quotes Father Merton’s The Wisdom of the Desert,

Some elders once came to Abbot Anthony, and there was with them also Abbot Joseph. Wishing to test them, Abbot Anthony brought the conversation around to the Holy Scriptures. And he began from the youngest to ask them the meaning of this or that text. Each one replied as best he could, but Abbot Anthony said to them: You have not got it yet. After them all he asked Abbot Joseph: What about you? What do you say this text means? Abbot Joseph replied: I know not! Then Abbot Anthony said: Truly Abbot Joseph alone has found the way, for he replies that he knows not.

Could the Sophists have taught how to achieve this, too? Here’s what Robert M. Pirsig had to say,

“Man is the measure of all things.” Yes, that’s what he is saying about Quality. Man is not the source of all things, as the subjective idealists would say. Nor is he the passive observer of all things, as the objective idealists and materialists would say. The Quality which creates the world emerges as a relationship between man and his experience. He is a participant in the creation of all things. The measure of all things...it fits. And they [the Sophists] taught rhetoric...that fits.

The one thing that doesn’t fit what he says and what Plato said about the Sophists is their profession of teaching virtue. All accounts indicate this was absolutely central to their teaching, but how are you going to teach virtue if you teach the relativity of all ethical ideas? Virtue, if it implies anything at all, implies an ethical absolute. A person whose idea of what is proper varies from day to day can be admired for his broadmindedness, but not for his virtue. Not, at least, as Phædrus understands the word. And how could they get virtue out of rhetoric? This is never explained anywhere. Something is missing.

…Plato’s Good was taken from the rhetoricians. Phædrus searched, but could find no previous cosmologists who had talked about the Good. That was from the Sophists. The difference was that Plato’s Good was a fixed and eternal and unmoving Idea, whereas for the rhetoricians it was not an Idea at all. The Good was not a form of reality. It was reality itself, ever changing, ultimately unknowable in any kind of fixed, rigid way. [Emphasis mine]. (Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Chapter 28)

From this ultimate unknowability, equanimity arises.

Not only that, but virtue does, too. As Sextus puts it,

…if one says that a system is a way of life that, in accordance with appearances, follows a certain rationale, where that rationale shows how it is possible to seem to live rightly ("rightly" being taken, not as referring only to virtue, but in a more ordinary sense) and tends to produce the disposition to suspend judgment, then we say that he [the Pyrrhonist] does have a system. (Outlines of Pyrrhonism, I.16-17)

Perhaps the ancient Pyrrhonists knew about the Dissoi Logoi’s influence on Pyrrho - that it was the urtext of Pyrrhonism. That’s why the text also influenced later Pyrrhonists. That’s why Zeuxis was remembered for writing a commentary on it (Diogenes Laeritius. IX.106). And that’s how this short, proto-Pyrrhonist text ended up being preserved along with the final Pyrrhonist texts from antiquity.

If you’d like to read the Dissoi Logoi, the text is just a few pages long. Molinelli’s 2017 Ph.D. dissertation is available online and contains an earlier iteration of his work. T.M. Robinson’s earlier translation is also available online.

thanks for the report, I'll just riff on my reaction reading it, it is not quite a comment, more a msuing,

in the trash-talking of sophist --- in the demeaning of sophisticated competitors -- I am reminded of the cries of obscurantism, when some more po-mo elements are used as tools. Or relativism. Not that dogmatic scepticism is not a thing in some deconstructionist frameworks.

The loyal disciple often hardens their conversion into a worlding reality, by refusing exceptions to purity, they know him, they know truth, thus, like rust, arete is eaten up by those who follow as they successfully market their fervour in-the-name-of, they just know