In Buddhism, “dependent origination” is an observation that nothing exists independently. As the Buddha explained,

When this is, that is. This arising, that arises. When this is not, that is not. This ceasing, that ceases. ( Samyutta Nikaya 12.61)

All objects and phenomena are brought into existence by other objects and phenomena, and their continued existence depends on other objects and phenomena. Things are the way they are because they are conditioned by other things.

The concept of dependent origination is not exclusive to Buddhism. As with many other Buddhist concepts, dependent origination can be found in the ancient Greek philosophy of Pyrrhonism, whose founder, Pyrrho, was a member of Alexander the Great’s traveling court on Alexander’s Indian campaign. Pyrrho spent a year and a half in India, where he picked up Buddhist ideas and turned them into a philosophy based on insights derived exclusively from rationality and empirical observation.

The ancient Latin writer Aulus Gellius describes the Pyrrhonist view as follows:

Therefore they call absolutely all things that affect humans’ sense “τῶν πρός τι”. This expression means that there is nothing at all that is self-dependent, or which has its own power and nature, but that absolutely all things have reference to something else… (Attic Nights XI: 5: 7)

The ancient Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus explains this further,

…since everything is in relation to something, we shall suspend judgment as to what things are in themselves and in their nature. But it must be noticed that here, as elsewhere, we use “are” for “appear to be,” saying in effect “everything appears in relation to something.” But this statement has two senses: first, as implying relation to what does the judging, for the object that exists externally and is judged appears in relation to what does the judging, and second, as implying relation to the things observed together with it, as, for example, what is on the right is in relation to what is on the left…. But it is also possible to prove by a special argument that everything is in relation to something … we have shown that all things are relative, the obvious result is that as concerns each external object we shall not be able to state how it is in its own nature and absolutely, but only how, in relation to something, it appears to be. It follows that we must suspend judgment about the nature of the objects. (Outlines of Pyrrhonism I.135-140)

Both Buddhism and Pyrrhonism use dependent origination to eradicate egotism and conceit. In Buddhism, dependent origination is extensively employed to highlight the illusory nature of the self. If the self is completely dependent on things that are not the self, then the self is a kind of illusion.

In Pyrrhonism, dependent origination highlights our tendency to rashly adopt beliefs. This leads to various delusions, including egotism and conceit. Getting rid of faulty beliefs eliminates egotism and conceit.

The Pyrrhonists point out that everything we perceive is limited by perspective. It is a grave mistake to jump from that which can be observed and understood from just one perspective to the conclusion that that perspective is the truth.

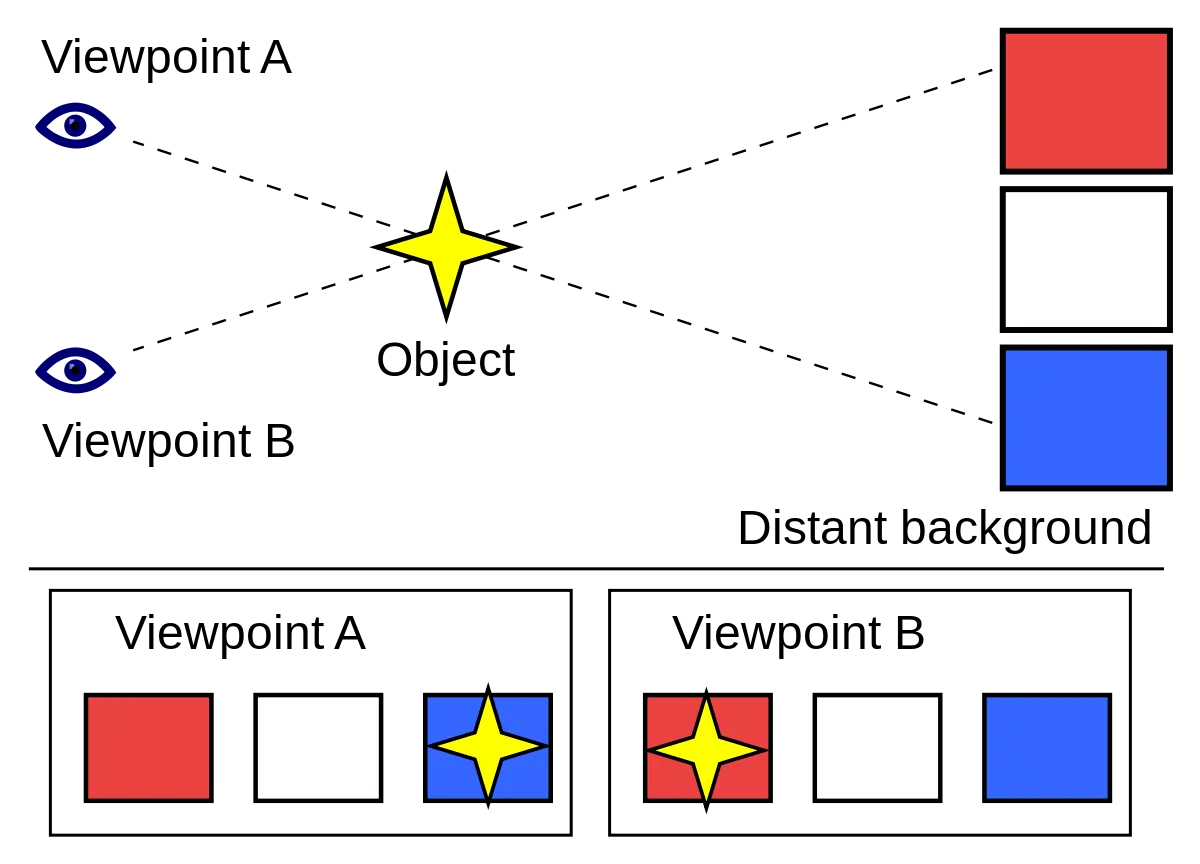

Here’s a useful diagram of the limitations of perspective.

From viewpoint A, one thing appears to be the truth. From viewpoint B, something different appears to be the truth. From the perspective we are given in this example, truth transcends both viewpoints, but those at viewpoints A and B don’t have access to this perspective.

This is a simple example based on viewing physical objects. Things get dramatically more complicated when the objects are abstractions, and even more so when the objects involve moral judgments.

In Pyrrhonist terminology, what is experienced from each viewpoint is an “appearance.” While people commonly think they can infer what the truth is from the appearances, the aim of Pyrrhonism is to demonstrate that this inference is insecure. For many people, this is a mind-blowing revelation.

The Buddhists also note this difference between appearance and reality. For example, the Dalai Lama described dependent origination this way:

"Once we appreciate that fundamental disparity between appearance and reality, we gain a certain insight into the way our emotions work, and how we react to events and objects. Underlying the strong emotional responses we have to situations, we see that there is an assumption that some kind of independently existing reality exists out there. In this way, we develop an insight into the various functions of the mind and the different levels of consciousness within us. We also grow to understand that although certain types of mental or emotional states seem so real, and although objects appear to be so vivid, in reality they are mere illusions. They do not really exist in the way we think they do."

From the Buddhist “conventional” viewpoint and the Pyrrhonist “apparent” viewpoint, the self exists. You can differentiate yourself from other people and from other things. From the Buddhist “ultimate” viewpoint, and the Pyrrhonist viewpoint about what lies beyond the apparent, the self is dependent on other things. It has no existence in itself. Change the things it is dependent upon, and the self is changed. The self has no essence; the self has no Aristotelian substance.

This lack can be illustrated through an ancient Greek paradox about the ship of Theseus.

The city of Athens preserved the ship used by its ancient hero, Theseus. Instead of putting the ship in a museum, they left it in the harbor, ritually taking it out to sea once a year. As with any ship exposed to the elements, the ship periodically required parts to be replaced. Over the years, every single part of the ship had been replaced. No part had ever sailed with Theseus.

Was it still the ship of Theseus? If not, when did it stop being his ship? Were all of the discarded old parts the ship of Theseus? But they were no longer a ship.

The self is like this.

The Buddhist emphasis here is that the self has no real existence. The Pyrrhonist emphasis is that whatever the self is, we cannot grasp it.

I recall a short talk given by a monk at Zen Mountain Monastery in New York state, in which she shared her feelings about coming to realize that she did not exist. While I intellectually knew the Buddhist doctrine here, the monk’s literal and very emotional interpretation of it felt weird, both then and now. It seems to be too much of a contradiction for most people to take seriously: who is it who is telling me they do not exist?

I think Pyrrho’s reframing of dependent origination was a wise move. This reframing made it into something that reason-fixated thinkers could embrace, such as the ancient Greeks and their intellectual descendants - us.

In ancient Athens, there was once a famous gadfly who went around exhorting people to know themselves. He also went around asking people to explain not merely what justice was in a particular case, but what “absolute justice” was. The gadfly’s intellectual descendants persist in this, not understanding that they are asking for the impossible. These things are all dependent upon other things. Infinite regress and constant change prevent one from ever fully knowing them.

I would point out that the Buddhist concept is also very closely related, if not identical, with the causal model of rebirth/samsara.

https://bswa.org/bswp/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Ajahn-Brahmali-Dependent-Origination.pdf

It is often, however, rebranded as "interdependence" by the West, which isn't quite accurate.

As for anatta being difficult to grasp (through teaching)... I believe it is quite beautifully (and somewhat humorously) elucidated in the Khemaka Sutta (SN 22.89) https://suttacentral.net/sn22.89/en/sujato?lang=en&layout=plain&reference=none¬es=asterisk&highlight=false&script=latin.

Very interesting and well written.

Thank you.